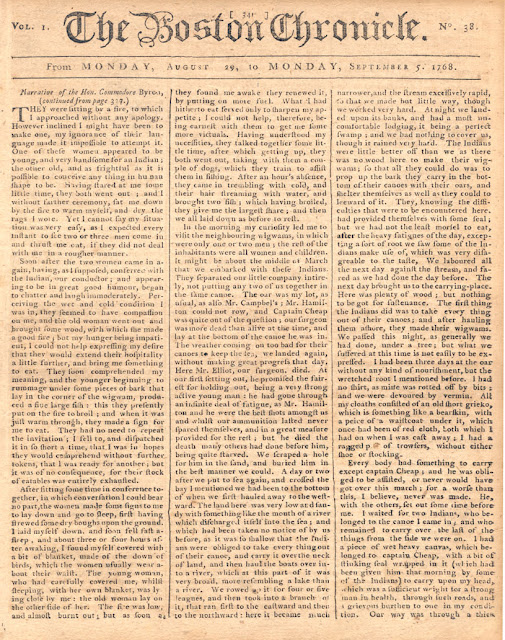

Starting with the October 9th edition of the Boston Chronicle, Mein took the gloves off and started making personal attacks on his enemies. He already had been called a number of things to include a "mushroom judge" and a "conceited empty noodle of a most profound blockhead" by merchants whose manifests he had questioned. Mein printed brief caricatures and gave nicknames to key popular leaders. Although he disguised their names, it was obvious who Mein was lampooning. John Hancock was "Johnny Dupe alias the Mich-Cow"; James Otis was "Counsellor Muddlehead, alias Jemmy with the Maiden Nose"; and Samuel Adams, "Samuel the Publican, alias The Psalm Singer, with the gifted face."

|

| John Hancock |

Meanwhile tensions had continued to rise in a Boston that had endured British army occupation for a year and found it increasingly difficult to contain its rage. In one incident in late October, an attempt to serve a warrant to a British Ensign of the 14th Regiment almost resulted in a bloody riot between civilians and soldiers when a British soldier fired his musket in warning and others thrust their bayonets in the face of a crowd that had gathered to witness the events. The Ensign and his Captain were indicted for ordering the troops to fire on civilians, but neither was convicted.

Mein, declared an outlaw by the town, and his partner John Fleeming took to carrying weapons.

At the same time Mein was facing a lawsuit that could be his ruin and he was thus under extreme pressure from two sides. John Hancock and John Adams were involved in an attempt to secure repayment of Mein's London debts. The details of that lawsuit will be presented in another installment.

In the October 26th issue of the Chronicle, Mein, in his infuriatingly sarcastic manner, placed, in the upper left corner of the first page, the names of six men he believed to be the merchants steering committee, mimicking the Boston Gazette's list of non-compliers. In this issue he also placed his now infamous caricatures of the popular readers.

In the afternoon of October 28th, the day the Chronicle appeared apparently having been delayed for two days, Mein and John Fleeming left their store, with each carrying a loaded pistol, and ventured into King Street. Their path was immediately blocked by a group of 10 to 12 persons of considerable stature, including the merchant Edward Davis, Captain Francis Dashwood, William Molineaux*, a leader of the non-importation movement and the leader of the Boston mob, and a tailor, Thomas Marshall, who also the Lt Colonel of the Boston Militia Regiment. Several of the men, to include Dashwood, believed themselves to be ill treated in the Chronicle. After exchanging angry words with the men, Mein pulled his pistol, cocked it, threatened to fire if they didn't stand off, and with Fleeming, who also pulled his pistol sometime during this confrontation, at his side backed up King Street continuing to shout that he would shoot the first man that touched him.

Sometime during this initial confrontation, a crowd, estimated by some to be over one thousand strong who had gathered earlier to tar and feather a suspected customs informer, arrived at the scene.

The crowd continued to stalk Mein and Fleeming as they backed their way towards the British Guard House near Town House; but the crowd kept out of range of the two printers' weapons. Cries of "Knock him down," and "kill him" reverberated through the streets and, with bits of brick flying, Mein and Fleeming finally reached the Guardhouse.There the soldiers let the two men slip to safety behind them. Mein would have escaped injury except for Thomas Marshall, the tailor and Lt Col of militia, who picked up a heavy iron shovel during the flight up King Street and swung it at Mein who received an ugly gash.

In the melee, either Mein or Fleeming discharged his pistol as they "retreated into the building" but no one was injured. The crowd believed it to be Mein, perhaps willing it to be so, but the evidence points to Fleeming.

As a crowd of 200 or so remained outside the guardhouse, Mein sent several messages to Acting Governor Thomas Hutchinson, demanding that the law come to his aid. Hutchinson did nothing, cautioning Mein to be careful since he realized that it would be suicidal for the volatile Scotsman to be seen again on the streets of Boston. Meanwhile Molineaux and Samuel Adams went to a justice of the peace and applied for a warrant to arrest Mein for firing a pistol during a peaceful assembly. They were accusing the wrong man but they got their warrant. When they showed up at the guardhouse with the warrant, Mein hid in the attic while Adams and others searched for him. After they left, Mein borrowed a British uniform and escaped to a Colonel Dalyrymple's house. He kept on sending messages prodding Hutchinson to provide protection but Hutchinson and his Council refused to use British troops to protect him or put down another disturbance.

|

| Thomas Hutchinson |

* William Molineaux's importance as a leader at this time should not be underestimated. But for his death in October 1774 , he would be remembered rather than forgotten.

** For a time, it was believed that Mein returned to Boston but it has been sufficiently established that he did not.

We are not through with Mr Mein, there are severall loose ends that must be wrapped up. In Part Five we will discuss the Pope's Day celebration in Boston.

.jpg)