David Hackett Fisher's marvelous book,

Paul Revere's Ride, certainly deserves the accolades and awards it has won. My main criticism of it is that it reads too much like a polemic; an argument to make Paul Revere more important than he really was. Was Paul Revere really a Patriot leader or was he a dedicated, if at times less than competent,

connector, as one historian characterizes him? A man who, because of his skills and profession, was able to move freely between social classes and serve as a conduit? But that is a discussion for another day.

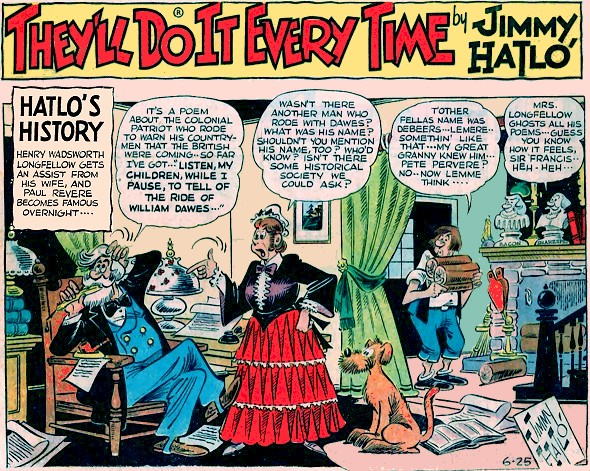

I would like today to focus on the night of 18-19 April, 1775, and the actions of Dr Joseph Warren in sending couriers out into the countryside to warn that "the regulars were out." We have to overcome the fact that Henry Wadsworth Longfellow has indelibly etched in our brains that it was "Revere's Ride" as opposed to "Warren's warnings" or "the night of the couriers"

There are a number of inconsistencies, inaccuracies, contradictions and mis-identifications in the various written sources for the account of Dr Joseph Warren's use of couriers to alert John Hancock and Samuel Adams in Lexington that the regulars were out and marching in their direction. We will never know all the precise details with dead certainty or, indeed, the actual number of couriers. Revere alone wrote three separate accounts of his famous ride and the original manuscripts have serious revisions and cross outs. In his book, Fisher resolves all of these in Revere's favor.

The other, somewhat prominent, courier Warren employed was William Dawes Jr and it's indicative of Fisher's purpose in his book in recalling just how Fisher introduces Dawes to his readers:

"One message had been entrusted to William Dawes, a Boston tanner. Dawes was not a leader as prominent as Revere, but he was a loyal Whig, whose business often took him through the British checkpoint on Boston neck. As a consequence the guard knew him. He was already on his way when Revere reached Doctor Warren's surgery. Another copy of the same dispatch may have been carried by a third man."

But just who was William Dawes, why did Doctor Warren make this 30 year old Bostonian his first choice to get through the British lines, especially using the very dangerous and longer route through Boston neck, and was he just some one whom Warren found handy?

|

| William Dawes Jr - Evanston History Center |

The Dawes family was well known and well established in Boston. The first William Dawes, a mason by trade, migrated to the colony in 1635, first settling in Braintree and then moving shortly thereafter to Boston, where he acquired a home on Sudbury Street that remained in his family for five generations until it was torn down by the British during the siege of Boston in 1775. William Dawes, Jr (Always titled Jr since his father outlived him) was born in Boston on 6 April, 1745, a little over a year later than Revere. He spent his childhood in his father's home on Ann Street in the North End. Nothing is known of the junior Dawes youth except that he learned the trade of a tanner and upon adulthood operated a "tan yard" in the North End. At the age of twenty-three, he married the seventeen year old Mehetabel May of Boston. They lived in a house opposite from the senior William Dawes and had six children. Prior to the Revolution, Dawes was elected to a number of minor Boston town offices such as warden and informer of deer. ( Boston had a number of these minor and obscure offices to be filled and many Bostonians, Samuel Adams amongst them, were selected to serve.)

|

Mehetabel May by John Singleton Copley who painted a number of Ms May's family and who was, at one time, a neighbor of Dawes.

|

In April 1768, Dawes joined, as had his father before him, the

Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts (originally titled the Military Company of Massachusetts) which is the oldest chartered military organization in North America and third oldest in the world. It was formed as a means of defense in 1637 by citizens of Boston who had been members of the Honorable Artillery Company of London. It received a royal charter in 1638 and then compiled a distinguished record. By 1768, the Company had been long established and had its headquarters in Faneuil Hall. Its officers were elected for one year terms and William Dawes, Jr. served as its second sergeant in 1770.*

In February 1768, two field pieces, brass three-pounders, arrived by ship in Boston. The guns had been recast from two old guns sent to London by the town for that very purpose. They had the province arms stamped on them and were to be used by the Artillery Company of Massachusetts. These two guns, along with two others, were stored in a "gun house "at the corner of West Street.

In January 1775, General Gage was confiscating military stores and a member of the Artillery Company vowed to surrender these guns to Gage. A number of the "mechanics" who belonged to the Company, believed to be led by William Dawes, were determined to prevent the guns surrender. One day in January 1775, the plotters, led by Dawes, met in a school house separated by a yard from the gun house. When the British sentinel guarding the gun house was distracted by a roll call, the plotters crossed the yard, entered the gun house, removed the guns from their carriages, and carried them to the school house where they were concealed under a box of wood. The loss of the guns was soon discovered and a search of the area was conducted to include the school house. The school master placed his lame foot on top of the box in which the guns were concealed and the British soldiers never disturbed the box. The guns remained in the schoolhouse for about a fortnight and escaped detection during several subsequent searches. They were then taken, under Dawes' supervision, in the nighttime in a wheelbarrow to a blacksmith's shop and hidden under some coal.

On 5 January 1775, The Committee of Safety directed that " Mr William Dawes be ordered to deliver to said Cheever [Deacon Cheever] one pair of brass cannon, and that the said Cheever procure carriages for said cannon__." Under these orders the cannon were sent to Waltham and were in active service throughout the Revolutionary War being used in a number of engagements.

In lifting a cannon from its carriage in the gun house, Dawes forced one of his sleeve buttons so deeply into one of his wrists that it became embedded. Dawes waited for a day or two not daring to show the wrist to anyone; but the wrist eventually became so painful that he had to seek medical help. The only one he could trust was Dr. Joseph Warren so he approached him. It's most likely that he and Warren were already well acquainted given their political views and the fact that they lived in the same neighborhood. When Dawes entered Warren's surgery, Warren asked him, according to Dawes' granddaughter, "Dawes, how and when was this done?" Dawes remained silent and Dr Warren finally said "You are right not to tell me. I had better not know." Warren was probably astute enough to put two and two together.

That Dawes was no friend of the British troops occupying Boston and was an ardent Patriot, there is little doubt. He scoured the countryside in an attempt to recruit allies and to obtain gunpowder. We do not know precisely the nature of these activities but, according to his granddaughter, " During these rides, he sometimes borrowed a friendly miller's hat and clothes, and sometimes he borrowed a dress of a farmer, and had a bag of meal behind his back on the horse."

And so on that fateful night of April 18th, 1775, Dr Joseph Warren had to find reliable couriers to get the word to Lexington. Who better than Dawes, a man of military training, if not experience ; a man Warren knew to be courageous, and who made forays into the countryside? Could Warren have used him for missions previously? We have no information about that but, then again, Warren didn't keep any records and was killed at Bunker Hill before he could tell all that he knew. But certainly, Warren would want someone reliable and who could be trusted without hesitation. And, indeed, the efforts of Dawes that night, in passing through a narrow gate closely guarded by British sentries who were suspicious of any travelers outbound through Boston neck certainly resounds to Warren's wisdom in selecting him. Dawes was remembered to have passed through the neck "mounted on a slow-jogging horse, with saddle bags behind him, and a large flapped hat upon his head to resemble a countryman on a journey." Obviously not the image of a romantic, dashing courier on a horse galloping through towns shouting at the windows of asleep villagers, but precisely the type of man a seasoned intelligence officer would send on this mission.

Just how Dawes got through the British sentries is not clear. Some accounts have him attaching himself to another party; others that he knew the sergeant of the guard and managed to talk his way through. One account reports that a few moments after Dawes passed through the British sentries, the guards received orders to stop all movement out of the town. Regardless, Dawes got through.

For the purposes of this post, we need not concern ourselves with the details of Dawes' journey after he passed through the neck. What we do need to note is that Dawes was a logical choice for Warren and he was not just some "tanner" picked to go on a vital and perhaps dangerous mission. I think that Revere's advocates somehow believe that praise for Dawes or any other courier somehow diminishes " Revere's Ride" and makes his ride through the countryside somehow less worthy or heroic. I don't. But I blame it all on that Longfellow fellow.

After Lexington and Concord, Dawes joined the militia forces in Cambridge and is said to have fought at Bunker Hill. In September, 1776, he was appointed second major of the Boston Regiment of Militia. When Boston became unsafe, he moved his family to Worcester where he was appointed Commissary by the Provincial Congress. He then went into business as a grocer with his brother-in-law and continued to ply that trade in Boston after the war. Somewhere along the way, perhaps as early as the 1770's, William Dawes injured his knee and became lame in one leg. He died at his father's farm in Marlboro on February 25th, 1799 and was buried in the King's Chapel Burying Grounds in Boston. Local Boston historians have recently determined that Dawes' body was moved a couple of times until finally, in 1882, it was interred in the May family tomb in Forest Hills Cemetery in the Jamaica Plain area of southwest Boston. There is no individual marker for Dawes. But, it gets even more unbelievable. Dr Joseph Warren's body was also moved to Forest Hills Cemetery in 1855.

Today, Dawes and Warren lie buried less than 200 feet from each other.

|

Forest Hills Cemetery

|

* Some historians have characterized Dawes as a "clerk" in this artillery company, perhaps in an attempt to denigrate him. In fact, Dawes was elected a clerk of the

Artillery Company at its revival in 1786, after the war was over. Before the war he was an active soldier even holding, at one point, the elected rank of sergeant.